Why Covid-19 is another blow for Kenya's food security

When all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic knocked on its door, the country faced a devastating desert locust invasion. This added to constraints posed by excessive rainfall experienced from October 2019.

The worst food insecurity that Kenya has faced in recent years was in 2017 and 2008. The food production deficit and food prices were their highest ever in these years.

The Kenya National Bureau of Statistics estimates that about 12 million people are food poor. These are people whose income doesn’t enable them to consume enough calories for a healthy lifestyle. Two-thirds of the food poor individuals are found in rural areas.

Kenya relies heavily on maize, wheat, rice and Irish potatoes for food. It is estimated that the country imports about 90% of the total rice demand and about 75% of the total wheat demand. The rest is produced locally. For example, Kenya produces most of the total maize demand itself, importing only about 10%.

A key challenge for the country is to raise productivity in the agriculture sector. This would not only ensure food availability, but potentially lift households out of poverty. To attain this, the country must reduce reliance on rainfed agriculture systems, use modern varieties and technologies by enhancing investments in extension systems, build resilience of farmers against the effects of climate change and variability, and improve agricultural market systems and infrastructure.

The coronavirus outbreak adds to the challenge because markets have been closed and delivery of food has been disrupted.

Immediate challenges

The 2019/2020 season was favourable with most parts of the country receiving above-average rainfall. But above-normal rainfall continued through the harvest period, with adverse effects.

The agriculture ministry now estimates that 10,000 hectares of cropland were destroyed during the long rain season alone. And post-harvest losses are expected to be higher than usual because grain didn’t dry adequately in the wet weather.

In December 2019, vast swarms of desert locusts started arriving in the country. By March 2020, the Food and Agriculture Organisation categorised the threat to the country as dangerous, because the locusts continued to breed and form new swarms.

This is the context in which the first case of Covid-19 was announced in March. Administrative measures have included the closure of produce markets and dawn to dusk curfews.

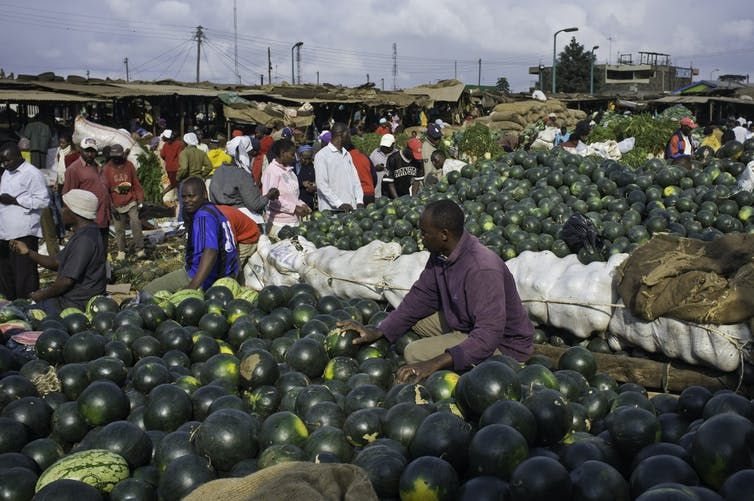

These were highly disruptive for food delivery. This is because Kenya’s food system is heavily dominated by small, independent transporters as the link between producers and consumers. Produce markets, which are at the heart of distribution in urban areas, serve consumers and smaller retailers. This traditional informal system accounts for about 90% of the market.

The closure of many of these markets in the urban and peri-urban areas, while a reasonable measure to avoid crowding, has disrupted food supply systems, especially for fresh produce. The impact is felt most in low-income urban households which rely on these informal food markets.

The same cannot be said for the middle- and higher-income families who can buy fresh produce from supermarkets and grocery shops, which remain open.

The ministry of agriculture has now agreed to categorise transport of foodstuff as an essential service, to improve food supply in urban areas. But this is not enough. If produce markets remain closed, supply systems still aren’t working fully. About 90% of fresh fruits and vegetables are sold through these markets. A further measure should be to ensure that markets remain open all day, although at reduced capacities.

The long view

There is no doubt that overcrowding must be avoided. But measures must be put in place to ensure that all people can access food.

The local government’s measures to close the fresh produce markets are perhaps an admission that it is very difficult to create order in the informal system. But it’s not practical to carry on with business as usual.

County governments and the ministry of health should allow produce markets to function. They could have different traders on different days, restrict the numbers of people at the market at any given time and ensure that the safe distancing guidelines are followed. Enforcement would come at a cost, but the benefits would be better access and less panic.

The other key question is the adequacy of stocks available in the country. The planting for the long rain season is underway. The ministry has sustained measures already put in place to control desert locusts which now are a threat to the new crop. Farmers also need access to inputs to ensure optimal production.

The ministry has also announced plans to import maize, about 4 million bags, following its food security committee’s assessment that the current stocks can last up to the end of April. The imported volumes represent slightly above a month’s cover, which is estimated at about 3 million bags.

Earlier planning for imports is commendable, especially since the pandemic has also disrupted global food supply systems. The ministry should step up monitoring of stock, prices and distribution systems to ensure that the government can step in where the market mechanisms fail.

The pressure of the Covid-19 pandemic will be felt even after the pandemic has been contained. Economists have already predicted a global economic downturn in 2020. Availability and affordability of food will remain a top priority for all countries.

Kenya must ensure that adequate safety nets will be in place for food security for households that will be devastated economically. At the same time it must continue providing support to producers to improve supply as far as possible.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source: The Conversation Africa

The Conversation Africa is an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community. Its aim is to promote better understanding of current affairs and complex issues, and allow for a better quality of public discourse and conversation.

Go to: https://theconversation.com/africaAbout Timothy Njagi Njeru and Miltone Ayieko Were

Timothy Njagi Njeru is Research Fellow, Tegemeo Institute, Egerton University.Miltone Ayieko Were is Director, Tegemeo Institute of Agricultural Policy and Development, Egerton University